Museo della Forma Urbis: discover the marble map of ancient Rome

Museo della Forma Urbis: discover the marble map of ancient Rome

| Last updated: April 2024 |

Visiting a city for the first time? Then, chances are you're using a mobile app or a traditional folded map to find your way around. Whether digital or paper, maps have become an integral part of our daily lives. We've grown so accustomed to using them that it's easy to forget the ancient Romans didn't have this convenience.

Instead, the Romans relied on written travel guides known as itineraria. These guides listed cities, villages, and other landmarks along the route, as well as the distances between each stop. They served as invaluable resources for travelers, merchants, and military commanders, providing essential information about the terrain.

Just remember, whether you have a map or not, all roads lead to Rome (Via Appia Antica).

The use of itineraria doesn't mean that illustrated maps weren't around. However, they were often more decorative than functional. The Forma Urbis Romae is (or was) a great example.

The Forma Urbis Romae, also known as the Severan Marble Plan, was an extensive map of ancient Rome engraved on 150 marble slabs. Sadly, only fragments of this monumental map have been uncovered, and they've been out of public view for almost a century. Now, the fragments have found a new home. As of January 2024, they're on display in their own museum (Google Maps), nestled within a newly established archaeological park.

The Museo della Forma Urbis sits in the Parco Archeologico del Celio (located on the Caelian Hill).

Forma Urbis Romae

Emperor Septimius Severus commissioned the Forma Urbis between AD 203 and 211. It was part of the reconstruction of the Templum Pacis (Temple of Peace), which was destroyed by a severe fire in AD 192.

Engraved on 150 marble slabs, the map measured approximately 13 meters in height and 18 meters in width. This means it covered a surface area of 234 square meters! With a scale of roughly 1 to 240, the map represented at least 13,550,000 square meters of the old city. The scale was also detailed enough to show the floor plans of both public and private buildings, including temples, baths, and apartment blocks.

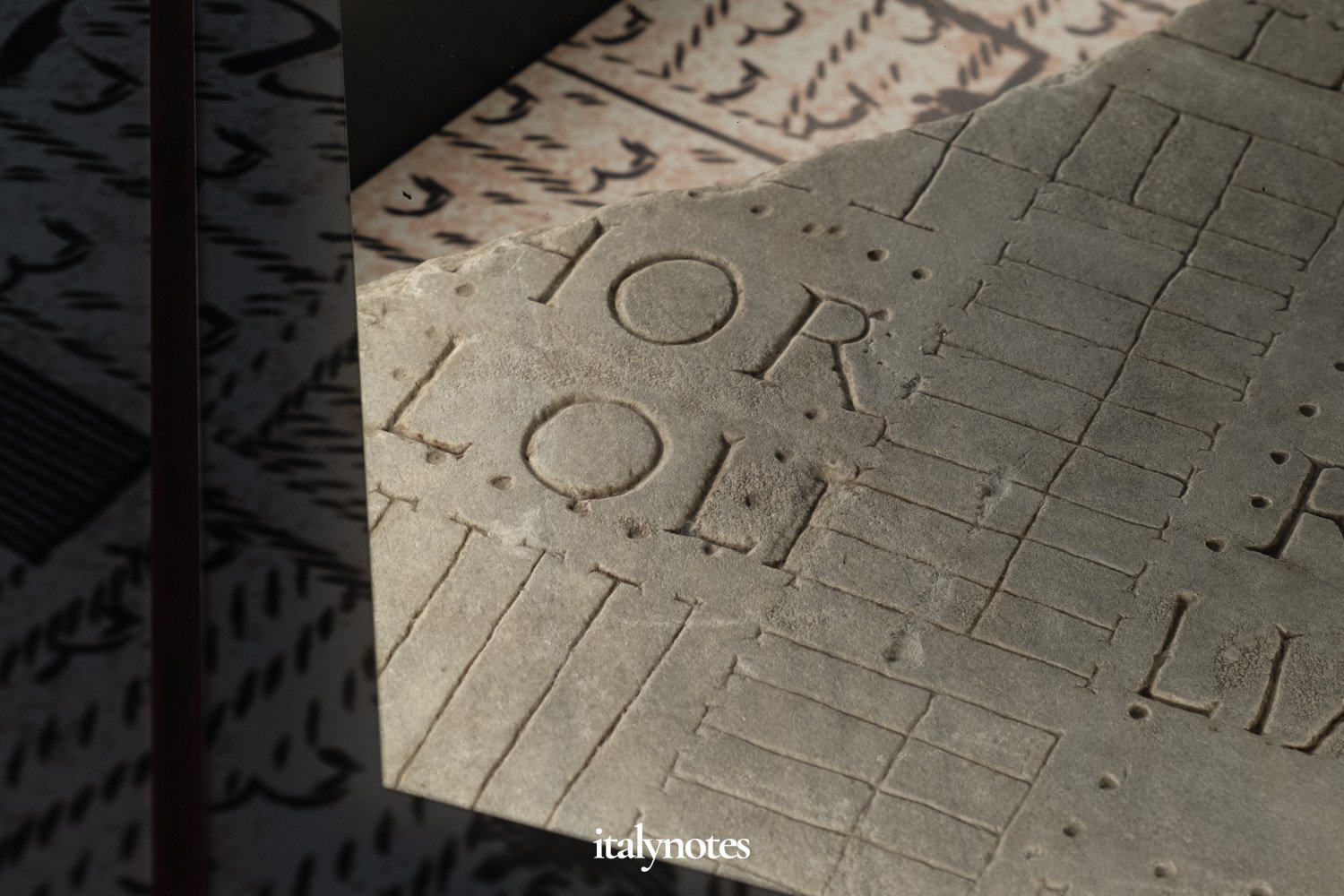

A couple of fragments depicting part of the Horrea Galbae. These warehouses (horrea) were situated in the southern part of ancient Rome and served as storage for the annona publica (public grain supply) as well as olive oil, wine, clothing and even marble. The fragment also depicts the tomb of Servius Sulpicius Galba. This tomb now stands in the Parco Archeologico del Celio, the same park where the Forma Urbis museum is located.

The Forma Urbis originally hung on a wall in the aula of the Templum Pacis. In AD 530, this same wall became the back wall of the then-newly constructed Basilica dei SS Cosma e Damiano. Fortunately, it remains intact today and is visible from Via dei Fori Imperiali (Google Maps). You'll immediately recognize the wall by the old mounting holes. They're remnants of the iron clamps used to attach the marble panels.

Fragments depicting the area between today's Palazzo del Quirinale and the Trevi Fountain.

The map's purpose

Standing before the wall where the Forma Urbis was once displayed, you'll fully realize the map's immense size. It also raises the question: How could one see the details at the top? After all, the map was 18 meters in height and started 4 meters above ground level.

Deciphering the plan's details, particularly at its highest point, must have been nearly impossible. But then, what's the point of having a map you can barely read? Today, the prevailing notion is that the marble plan offered a broad overview of the city, allowing observers to admire Rome's grandeur. One could argue that the map's function was more about propaganda than practicality.

The wall that once displayed the map remains intact today and can be seen from Via dei Fori Imperiali. Standing in front of the wall, you'll fully realize the enormous size of the map. It becomes apparent that deciphering the plan's details, especially at its highest point, must have been impossible.

Destruction and discovery

During the Middle Ages, the Templum Pacis was abandoned and gradually deteriorated. Many of the marble slabs were 'robbed' for reuse as building material or for the production of lime. The remaining slabs gradually fell from the wall and were buried at its foot over time.

It wasn't until 1562 that several fragments of the Forma Urbis were discovered during excavations near the Basilica dei SS Cosma e Damiano. The discovery sparked excitement in the scholarly community, as the marble fragments seemed to be remnants of a significant Roman monument. However, the enthusiasm was short-lived due to the loss and dispersal of many pieces.

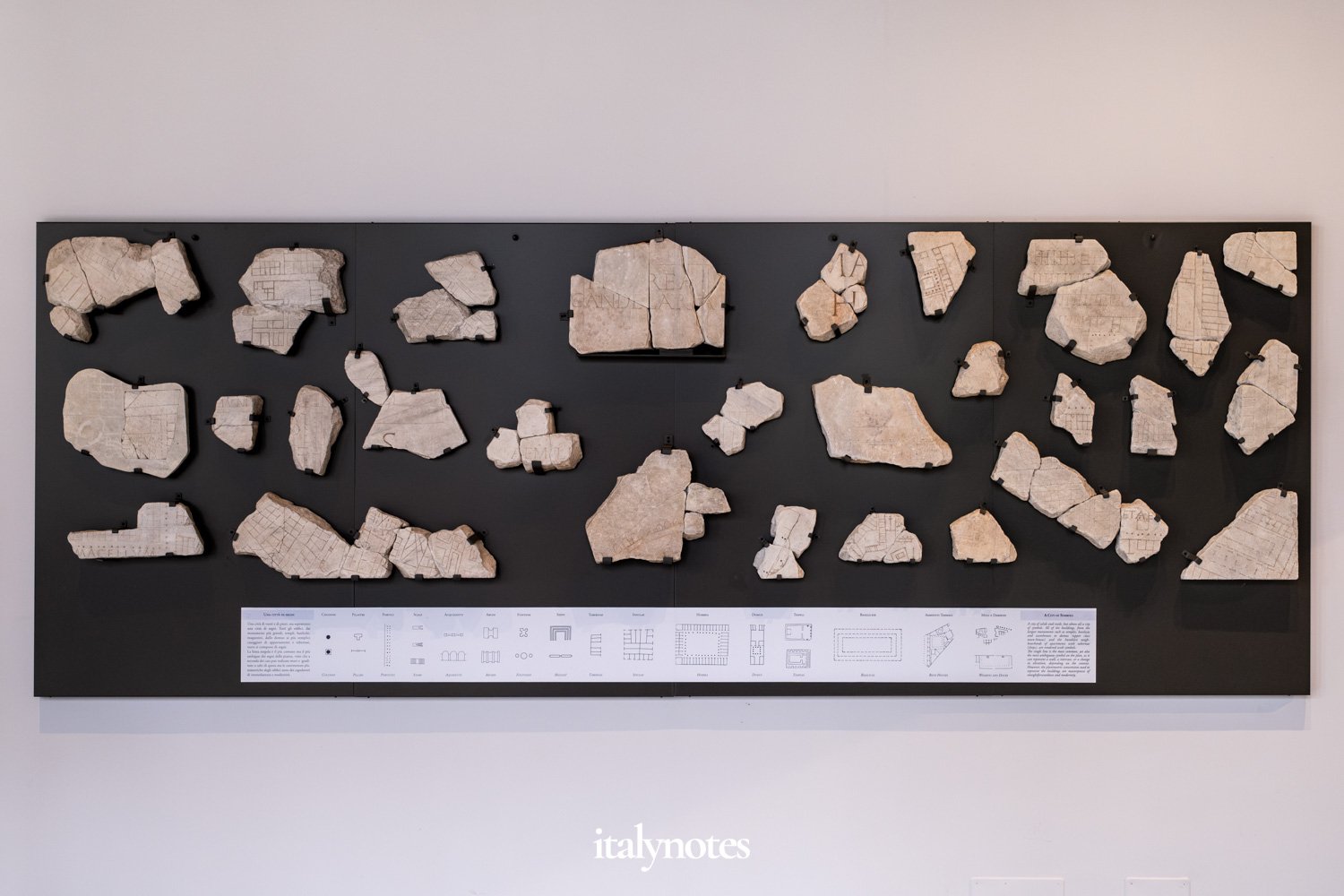

Mounted on the museum's wall are some fragments of the map whose placements are uncertain. They are combined with an explanation of different symbols found on the Forma Urbis.

The marble fragments were stored in the basement of Palazzo Farnese and largely forgotten. Many even got used (again) as building materials. Fortunately, in 1673, renewed interest in the map arose, leading to the relocation of the fragments to the Capitoline Museums.

Since then, several other fragments have been found throughout Rome, and scholars are still trying to identify their original placements. Among the hundreds of fragments discovered over the centuries, just about 200 have been identified and positioned. Reassembling the map is extremely difficult because most fragments are missing. Today, only about 10% of the marble map remains.

Two fragments of the Forma Urbis that still need to be identified and positioned.

Museo della Forma Urbis

As of January 2024, the remains of the Severan Marble Plan have their own museum, the Museo della Forma Urbis (Google Maps).

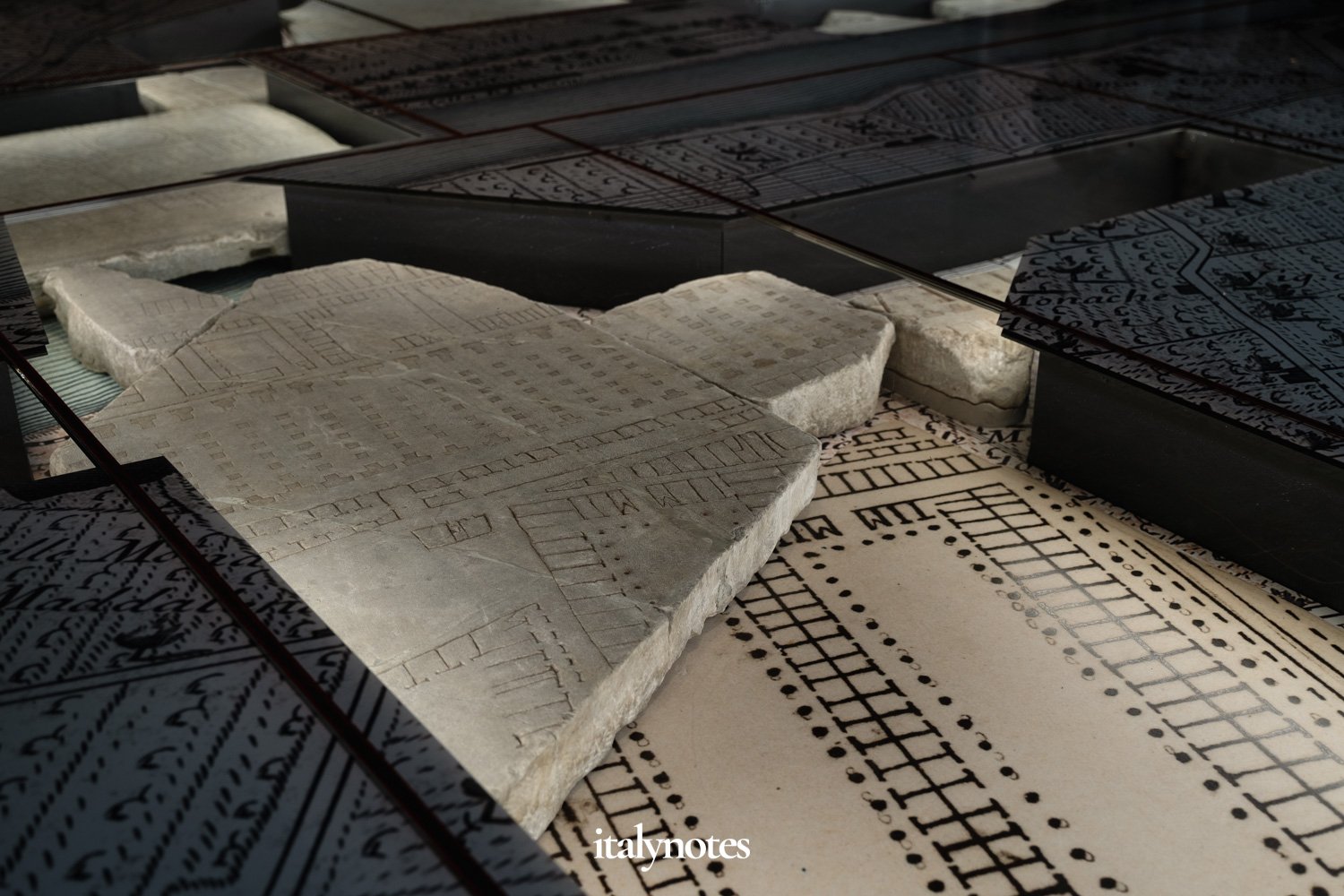

The roughly 200 identifiable pieces are superimposed on a copy of another map: Giovanni Battista Nolli's map of Rome (1748). Nolli's map is widely regarded as a masterpiece of cartography. It's the result of extensive sectoral surveys conducted on a large scale and depicts the city's buildings, churches, street furniture, and gardens.

Superimposing both maps allows visitors to orient themselves and navigate through the streets of the ancient city.

In the new museum, the Forma Urbis is exhibited on the floor, providing a sense of the original map's immense size and allowing a closer look at all the details.

Because the Forma Urbis is displayed on the floor, it allows for a closer look at its details. You can even spot some of the mistakes that were made. For instance, the 'Horrea Lolliana' inscription shows a possible miscalculation. There are traces of a second 'L,' but the engraver likely realized it would overlap with the plan. Another mistake is visible in the 'Septizodium' description, where the engraver corrected the initial diphthong from ' SAE' to 'SE' with a very oblique 'E.'

The 'Horrea Lolliana' inscription shows traces of a second 'L' that would overlap with the plan.

Parco Acheologico del Celio

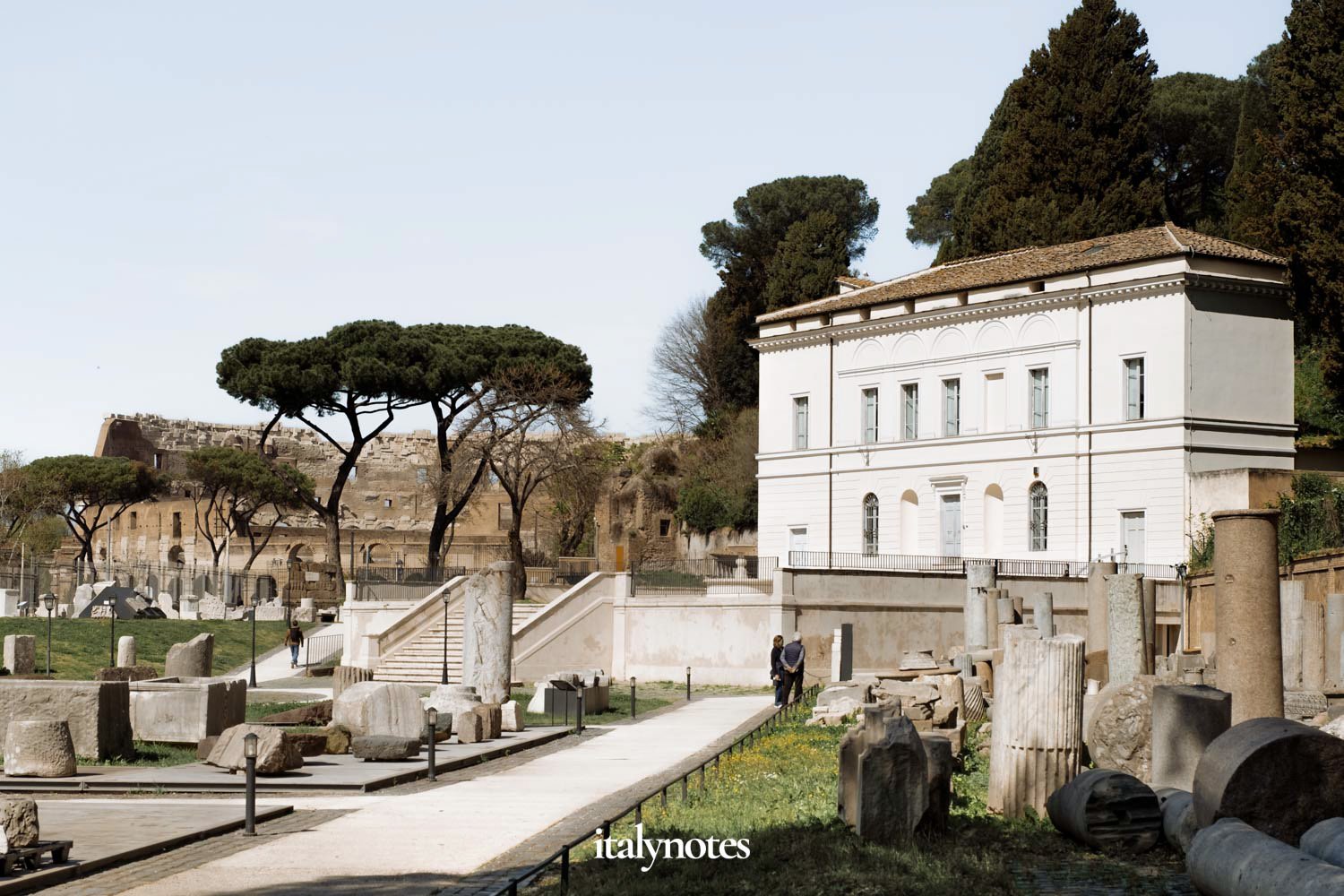

The museum sits in the Parco Archeologico del Celio, which covers the northwestern part of the Caelian Hill. In 1835, Pope Gregory XVI transformed this area into a public park and commissioned architect Gaspare Salvi to design a coffee house for visitors.

Today, the coffee house, known as Casina del Salvi, remains at the heart of the park and is sure to catch your eye. Unfortunately, the Casina is now closed, but the municipality intends to restore and reopen it soon.

The Casina del Salvi with the Colosseum in the background.

In addition to the Casina del Salvi, the park houses many archaeological artifacts from excavations conducted in the 19th century. On the left side of the Viale Parco del Celio entrance, you'll encounter several 'cippi.' These stone pedestals once marked the Tiber's riverbed and the extensions of the pomerium, the city's religious boundary.

Starting from the cippi, a path unfolds adorned with numerous tombstones. At the path's end, set against the backdrop of the Colosseum, stand two reconstructed tombs: those of Galba and Terentilius.

The park houses many archaeological artifacts from excavations conducted in the 19th century.

Near the northern gate, tucked into a small corner, you'll discover several other cippi. These stones once indicated the path of aqueducts.

The park's other half (on the entrance's right) features an exhibition of architectural materials. Part of it tells the story of building construction and decoration, while the other part showcases marble working techniques. Noteworthy in this section are two fragments of a coffered ceiling found in the area of Montecitorio, together with a monumental Corinthian half-pilaster capital.

One of the cippi that once indicated the path of an aqueduct (left) and another (unidentified) artifact (right).

Lastly, a collection of artifacts introduces the theme of reuse and rework, a phenomenon present throughout the city's architectural history.

The park may be small, but it's free to enter. Combined with a visit to the Museo della Forma Urbis, it's a great way to learn more about ancient Rome!

Practical information

|

|

Discover the rest of Rome