Bocche di Leone: stone letterboxes for accusations and betrayal

| Last updated: January 2025 |

Not too long ago, I shared a post about Venetian politics, including a paragraph on the powerful Council of Ten and how they gathered their information. One of their techniques, in particular, caught my attention and prompted me to learn more, revealing an intriguing aspect of Venice's history. Here is what I discovered.

If you take a walk through Venice's streets or visit the Doge's Palace, you might spot some peculiar stone carvings — an open-mouthed (lion's) face staring out from a wall. At first glance, it seems like just another decorative detail, but these faces, known as 'Bocche di Leone' or Lion's Mouths, held a much darker purpose.

Two surviving Bocche di Leone, removed from the walls, are on display in the Chamber of the Three Head Magistrates (placed in the room's fireplace) inside the Doge's Palace. You'll need to book the Secret Itineraries tour to visit this room.

These mouths were the city's tip-off boxes, where anyone could report crimes, conspiracies, or betrayals. Imagine living in a place where anyone could write your name on a slip of paper, accuse you of some heinous act, and drop it into one of these mouths. It could completely change your life — or even end it.

But how did the Bocche di Leone actually work? Were they an effective tool for justice, or more of a weapon for personal grudges and vendettas? And why are so few left today? Let's dive into the secrets of these sinister letterboxes.

Not just a letterbox

In 1310, Baiamonte Tiepolo, a young and rebellious noble, tried to restore power to the lower classes by plotting to overthrow Venice's government. However, his plan fell apart due to betrayal, poor planning, and a lack of support. The rebels were stopped near Piazza San Marco by forces loyal to the Doge. Tiepolo had to surrender and ended up exiled to Istria.

The plot against the Doge led to the creation of the Council of Ten, tasked with protecting the Republic from future threats. To do this, they used secret funds, anonymous informants, police powers, and wide-reaching authority over state security. But they introduced something else too — the infamous Bocche di Leone.

Tiepolo's house was demolished and a column of infamy was erected bearing the words: "This land belonged to Baiamonte and now for his iniquitous betrayal, this has been placed to frighten others, and to show these words to everyone forever." Nowadays, the column is on display in the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia. A humble stone plaque now marks its former location, reading: "Loc. Col. Bai. The. MCCCX.", meaning "Location of column of Baiamonte Tiepolo 1310."

The name 'Bocche di Leone' comes from the stone reliefs of a lion's face, symbolizing Venice and its patron saint, San Marco. While there were alternative designs, like a man with a threatening expression, the lion's face prevailed across the city. Instead of a mouth, there was a hole where people could drop in paper documents with information, reports, or accusations against those who committed a crime.

The Council of Ten placed the Bocche di Leone in each sestiere (district), often in the walls of churches. The Doge's Palace had several of these letterboxes as well, located in places like the loggia, the Sala della Bussola, and the Sala della Quarantia Criminale. Each box dealt with a specific issue or crime, such as taxes, blasphemy, fraud, trade disputes, or plotting against the State.

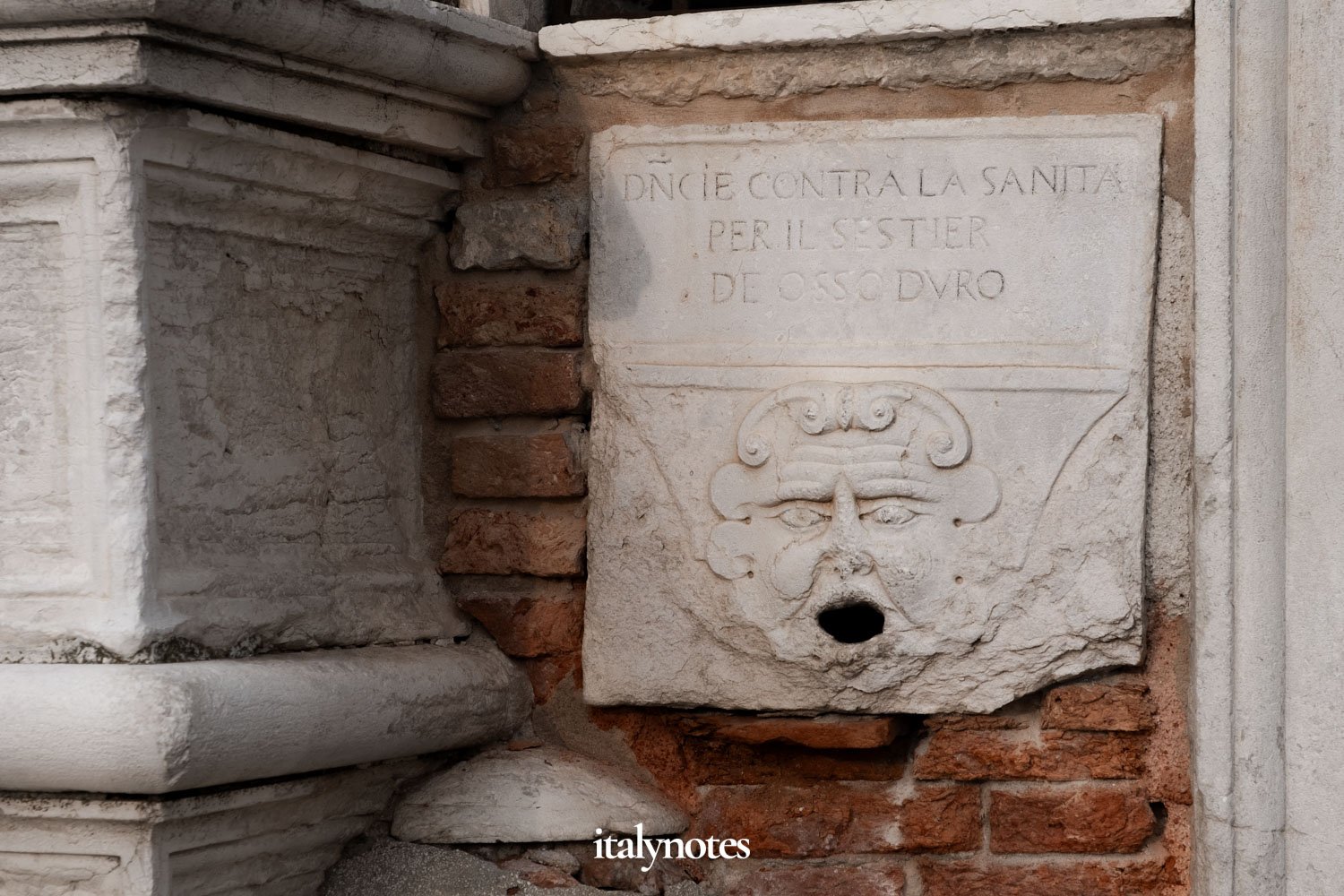

The Bocca di Leone for public health issues (in the Dorsoduro district) is located in the wall on the right next to the Chiesa di Santa Maria della Visitazione.

One box in particular reminds me of the COVID period: the complaint box for public health issues. In the 15th century, people stuffed it with letters during outbreaks of the Black Death, especially when they suspected someone had the disease. Authorities sent the infected to the quarantine island of Lazaretto Vecchio.

Anyways, after dropping a letter in one of the Bocche di Leone, it landed in a locked wooden box designed to securely collect all the complaints. The Magistrates held the keys to these boxes, and only the heads of each district could unlock them.

One of the walls of the Compass Room (Sala della Bussola) inside the Doge's Palace once featured one of these special letterboxes. You can still spot the spot where it was mounted (left). On the opposite side, you'll find the wooden box designed to securely collect all the complaints (right).

System of accusations

You might assume this system was perfect for people with personal grudges who wanted to make false accusations. But it wasn't, at least not entirely.

Each accusation had to be backed by proper evidence. But perhaps most importantly, it was impossible to accuse someone anonymously. Every letter had to be signed by the accuser, and the complaint had to name at least two reliable witnesses. In 1387, the Council of Ten ordered anonymous accusations, lacking the accuser's signature or trustworthy witnesses, to be discarded and burned.

However, there was one exception: accusations of possible conspiracies against the state could be made anonymously without being dismissed. Ignoring such claims could jeopardize the stability of the Republic.

The Chamber of the Three Head Magistrates. Chosen each month from the members of the Council of Ten, these three magistrates prepared court cases and ensured the swift execution of the Council's rulings. This room is part of the Secret Itineraries tour.

When the Council of Ten considered an accusation, they gathered more evidence and investigated further. Accusers found lying faced serious consequences. On the other hand, when the council found the accused guilty, they sentenced them to imprisonment in the city's notorious prisons, exile, or even death.

In part because of the Bocche di Leone, Venice had a strict and relatively effective legal system. However, it wasn't flawless — sometimes innocent people were condemned.

One of the old prison cells, where three to four inmates would typically be crammed in. Pretty cozy, right? You can see this particular cell during the Secret Itineraries tour, but there are plenty of other cells to check out during a regular visit to the Doge's Palace.

Surviving examples

In 1797, Napoleon Bonaparte took control of Venice and ordered the destruction of many things that symbolized the Venetian Republic, including several Bocche di Leone.

Luckily, a few managed to survive and are still there to admire. The first one I know of is in the wall of the colonnaded loggia of the Doge's Palace. Both this wall and the one in the Palace's portico also hold remnants of erased Bocche di Leone.

Another intact example is next to the Chiesa di Santa Maria della Visitazione (Google Maps). It's the Bocca di Leone related to public health issues that I mentioned earlier.

Some (remains of) Bocche di Leone in the wall of the colonnaded loggia of the Doge's Palace (top and bottom left), and the Bocca next to the entrance of the Chiesa Parrocchiale di San Martino (bottom right).

I know of a third Bocca, close to the Venetian Arsenal entrance of the Chiesa Parrocchiale di San Martino (Google Maps). I've read there's also a Bocca di Leone at the Torcello Museum, but I haven't seen that one myself.

Besides these intact Bocche di Leone, there are also some removed ones. Among them are those mentioned earlier in the Chamber of the Three Head Magistrates, and you can also find one in the Correr Museum. Lastly, on the right side of the Chiesa Parrocchiale di San Pantalon (Google Maps), there are traces of an erased Bocca.

Bocca di Leone at the Correr Museum.

It's interesting that, maybe as a nod to the past, The Department of Legal Studies of the Ca' Foscari University (Google Maps) has a letterbox in the style of a Bocca di Leone. And it's not the only one. If you stroll through Venice and keep an eye out, you'll certainly spot a few more.

If you spot any I missed, just let me know, and I'll add them here!

The letterbox of the Department of Legal Studies of Venice's Ca' Foscari University (left) and a random letterbox I came across near Ca' d'Oro (right).